Published on: May 20th, 2014

Last updated: December 21st, 2016

Best known as a presenter on the BBC documentary Big Cat Diary, Jackson Looseyia has almost 30 years of experience as a safari guide, while endeavouring to conserve the land and educate the local community. The guide, conservationist, educator and TV personality tells us his story.

In the past you’ve said that your family have been a big influence in your life and the direction you took. Tell us how.

My father, who was of Itorobo origin, lived in the Mara Region all his life, from the Loita Forest to the Serengeti plains and the high plateau of the Siria encampment. He led a nomadic life hunting and gathering honey in the Mara savannah, but with new administration under the rule of colonial British, he got into a lot of trouble for hunting [after imprisonment, he was subsequently made head ranger for his skills].

The warden, a tall, strongly-built man called Temple Borun – as my late papa described him – loved wildlife, and while my father worked with him, he got the message of the wildlife’s importance. He passed these words on to me and growing up I was taken to national parks in the Mara, Nakuru, Loita Forest and Nairobi. I was just a kid but I may have some pollen grain in my blood, as that’s when the idea of wildlife conservation in my life began.

What was your childhood like and how did it influence you?

After my father left the wildlife service, he continued his life of gathering, with some hunting to provide for our family. We had goats and cows from my Maasai mother’s side. I had to learn Maa and Iltorobo, but my Catholic school life was very different indeed.

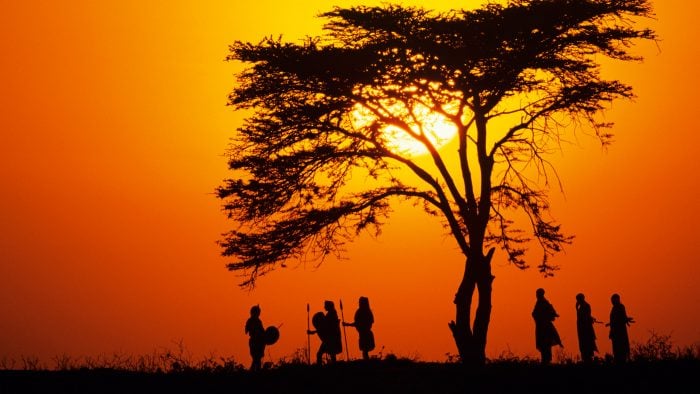

The Maasai population in the ‘70s and ‘80s was small. We were free and our area was huge, so as young boys we’d travel to look for roots to eat, to catch baby impalas and young Tommies [Thomson’s Gazelle], just for fun and to release afterwards. We learnt the different colours of the birds eggs, how to name species of birds and plants, how to climb trees, over rocks and up cliffs in search of honey and wild fruits. Then, in the evenings we would have to finish our homework.

All of this was exciting, with something to look forward to everyday, especially school, where our teacher would send us out to find samples for our science class – roots, seeds, bones and horns – just imagine young kids running wild in the woods full of wild and dangerous buffalo. I knew then that I loved the wilderness.

In 1979 we went on a Mara tour; I could not sleep or eat properly, as I was so excited to see wild animals up close. We met elephants, giraffe, buffalo, hippo, crocks and lions, and the funny thing was, no animal ran away from us.

Your father took you into the bush for six months to learn how to track the wild animals when you first reached manhood. What was that like?

I was first told by the elders. We are told as young men that you should never show pain, and that even if you get cut with a knife or hit by a spear, you have to be strong and fearless – brave enough to take down anything, even a lion. We had little debates between ourselves about whether it was good to be a girl or boy, but as boys we knew we had to be men and that the nation of Maasai people was in our hands.

Just before my first bush training, we had some ethnic wars, and I was not allowed to go alone, so my father took me and taught me how to treat arrow shots and handle spear wounds. I had to learn to obey my father as part of my training from the elders. In those days, when we ran, our legs were so strong and we jumped so high.

Were there any moments in the bush that you were afraid?

When I had to be taken, it was so early that even my Mother did not see me leave – sometime before we could tell the difference between the trees, shadows and man.

My father asked me to sit down for prayers, and it was at this moment that I knew we were far from home. We couldn’t be seen by anyone – including the wild animals and birds – and no noise was allowed. We had to walk like shadows and I still remember the silence. I was scared I would not return home to my mother and sister, and I had left my friends to be with wild animals that are deadly.

My late old man kept pointing out fresh buffalo footprints and pointing to the trees we could climb if a situation arose. When we went on adventures to lions’ and hyenas’ dens, I was so scared, my eyes were like a hare’s, but my father kept telling me to be strong, become a man and live long. His words are still alive today.

My biggest fear was of the lions, buffalo and elephants. I knew that if they charged, I would leave my father to fight on his own, and those are not the qualities of a man. I prayed not to meet them on foot, but I did, and so the stories continue.

You call Ron Beaton (a safari lodge owner at the time of meeting Looseyia) your mentor. Tell us about your connection to him. What did he teach you?

Four years later, I knew that I should start taking some responsibility, but still relied heavily on my father. Ron, who was the first conservationist in the Maasai Mara had employed my papa as a tracker while he led walking safaris. Ron was a strong character, well known in the Maasai land for his leadership and as a no-nonsense man. When Ron and my father talked they were like brothers and had a lot of stories to share, so I sat and listened, taking it all in.

One day Ron asked my father if I could join him to be trained. The spark started from there. Ron was a great man, who took me to every corner of the Mara and taught me how to be successful, in business and the real business of looking after the wildlife. I have never forgotten his words of wisdom.

What do you do to conserve the environment now?

I’ve now become well known through my training in the village and schools, and as a business partner of Ron and his son Gerard, so local people see me as a good example. I engage myself in the creation of conservancies. There are sleepless nights when we see a decline in wildlife areas or meet up with prides of lions with spears in them. Sometimes we encounter conflict with the Maasai killing animals, and sometimes I have to talk to the Government. All of this is preparation for creating Mara conservancies. After the success of these conservancies, it’s starting to work.

You also teach at schools in the Mara. What do you want people to learn?

I want people to learn that the Mara is unique and special – we have so much to offer, from the largest elephants to the smallest ants in the cracks of earth. They are here and we must look after them for the Maasai children, Kenyan children and other children around the world. It’s special.

How have the Maasai Mara and wildlife numbers changed in the time that you’ve been there?

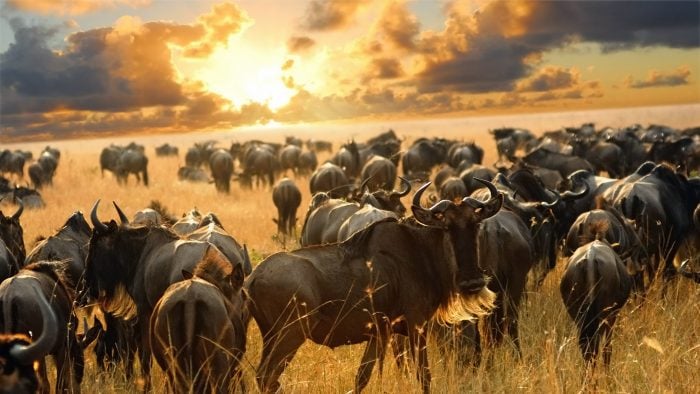

From the ‘70s I have seen a lot of changes in the Maasai Mara, from wildlife corridors shifting to corridors closing completely. I have seen the number of predators decline, from large prides of up to 30 or 40 to just two. I was sad, but not long after the conservancies came back, I saw a way out of this decline. Prides in the Mara conservancies are gaining glory.

You’re well known as a presenter on the BBC documentary Big Cat Live. How did you become involved?

I did not know the power of TV, so it took me a while to realize that this was big news, When I was guiding at Rekero Camp, I received a call from Nigel Pope asking for directions to come and meet me. When he arrived, we drank tea under an acacia tree, and he asked me if I would be on Big Cat Diary. I knew Simon King and Jonathan Scott and wanted to join them. I was excited, but at the same time scared at what my community would think. I said that this was one mountain I had to climb in life.

Can guests at Rekero Camp still be guided by you?

I’m now freelance so I can guide at Rekero Camp, among other safari camps.

What do you find most rewarding?

When I meet a guide who I knew as a kid, I know that the Mara has new ambassadors, and that what I have planted has grown. Secondly, when I see young cubs running around with no fear of man, I know that the future is bright for our children.

Have there been any especially memorable moments?

Seeing hundreds of Maasai people celebrate the birth of Naboisho Conservancy was one of the best moments I’ve had – children, women, and men were running with joy. It’s also when I see the Great Migration of wildebeest and zebra, blanketing the Maasai Mara plains. Long live the Mara and its species.

What plans do you have for the future?

I have to continue to create conservancies, as well as guiding in the Mara and other parts of Eastern Africa. I would like to learn more – education has no end and the stories continue.