Published on: May 14th, 2015

Last modified: February 16th, 2024

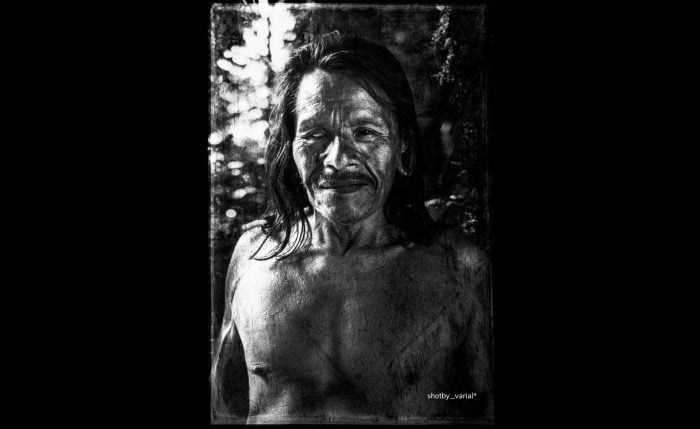

While staying with the remote Bameno tribe, photographer and director Cedric Houin discovers the cultural transition of an indigenous community entering the modern world.

It was in 2010 that photographer and director Cedric Houin, also known by his pseudonym Varial*, decided to devote himself to exploration and documenting the reality of the world’s disappearing cultures. While most of his projects are for NGOs, Cedric has been working on the ongoing personal project Contacted Tribes since 2013, looking into the issue of oil extraction from Yasuni National Park in Ecuador, and what it means for the indigenous people left with an area called the intangible zone.

“I landed in Ecuador for an unknown journey, but knowing that I wanted to get the voice of the tribes on the protection of their territory, their evolution and their future,” Cedric tells us. “This project doesn’t only tell the story of oil exploitation but it’s much more about the fight and challenges of one tribe – the Bameno people – who are caught up between what they want to defend, why they want to defend it and life as a modern tribe.”

“Culture is the last weapon tribes worldwide have today to fight for their land, their territory and their community.”

“From an occidental point of view,” he continues. “It’s a critic of how we still fantasize about the image of tribes, which is a problem in photography, TV and cinema. These tribes now play a game of images too, which is something they have to do. Culture is the last weapon tribes worldwide have today to fight for their land, their territory and their community.”

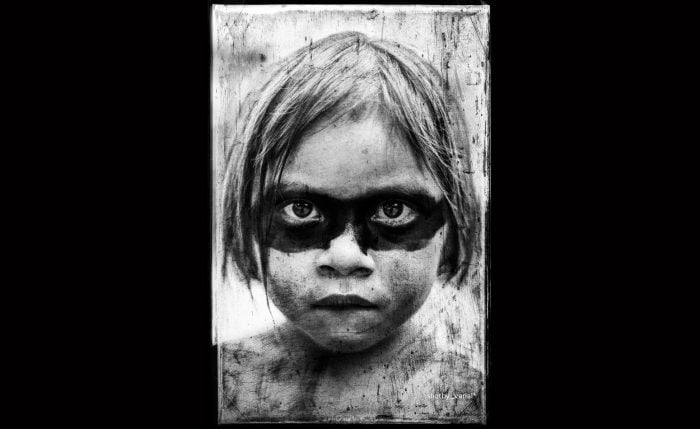

The title Contacted Tribes is a play on words with the notion of uncontacted indigenous people that’s in the anthropological world. “There’s still a quest for uncontacted people, so you see sensational photography of tribes who are naked and have never met strangers, but what’s the consequence of contacting these people and what do we want to change? After two generations the culture and language is lost and the kids don’t want to wear traditional clothes anymore.”

“Contacted is a reflection of what we should do with the 400-million indigenous people in the world and how we need to save their cultures, languages and traditions, because on their own these people won’t save it for themselves, they’ll try to fit into the modern world.”

The Huaorani people of Bameno

“I was told about the Huaorani community of Bameno, and I’d read about them, as the furthest, most remote and isolated tribe in Ecuador. I was born with that fantasy of the forest and tribes, so while keeping the documentary perspective, it was a personal quest too.”

Cedric began his journey in the Amazonian city of Puerto Francisco de Orellana – also known as Coca – the gateway to the jungle. In recent years the Bameno people have had motorboats to reach the city in two days, when it previously took between one week and 10 days.

“I knew about the chief of the Bameno people, so I stayed in Coca and waited for him to to show up,” Cedric explains. “The chief speaks Spanish. He learnt to read and write and can explain all of the oil developments on a map. He gets invited to the political conferences and is now the leader of a very modern fight. We managed to meet and I told him what I wanted to do, then he took me back with him and I spent a month with them in the forest.”

“Most of the tribes in the jungle in Ecuador have been contacted already, so the notion of contact doesn’t even apply anymore.”

“Most of the tribes in the jungle in Ecuador have been contacted already, so the notion of contact doesn’t even apply anymore,” he says. “It’s the third or fourth generation now that has lived in the modern world with traditional ways of living. The Bameno tribe want to retain their tradition but I want to question our role in their journey and our responsibility to not just being a witness to their culture disappearing. They have not lost their beliefs but they don’t speak about them that much.”

The first surprise for Cedric was arriving in the village and realising how modern it was compared to the images he’d seen portraying a primitive way of life. “When I arrived I saw that they had clothes and hardwood homes. I’d seen shots in which the people were all pictured naked with leaves, but they don’t live like that. They have shorts and T-shirts and boots. It’s far from the reality of these people, so my project is playing on all these contradictions.” Cedric continues to explain that while the tribe is in transition, you still feel the strong connection they have to their culture. “They are hunters, they are warriors, and they are very proud of what they are,” he proclaims.

“They like to hunt with their spears – even the kids play with spears – but now they have shotguns to hunt with too. I was surprised how badass the kids were, in a great way. They will fight and they are very proud of defending their territory.” In Bameno, the same word is used for both culture and territory.

Each family in the community provides for itself, so each morning members of the community leave to go hunting in the forest with a spear, and each family goes fishing, but they now also go to the city to buy food. “They are very connected to nature and they are very strong, healthy people,” Cedric says. “The shaman in the village would go out hunting in the forest and he’s 90 years old.”

“They are hunters, they are warriors, and they are very proud of what they are.”

Being with the Bameno people made Cedric realise how fast the modern world enters these communities as soon as electricity arrives, as electricity is soon followed by the arrival of TV. “In Bameno they didn’t even know the outside world 50 years ago, but now they have a big TV with 3D lenses because there’s a generator in the village. When TV arrives, so do the products, commercial music and trends. They watch a lot of novellas [soap operas] and TV shows like The Voice, so the kids all want to go to the states.”

“When I left the village, I asked the chief what development he wanted most there. When he said the Internet, I wasn’t surprised, because as the leader of their tourism and the defence of their territory, he goes back to Coca every week or two just to manage his emails and he’s bored of travelling for two days along the river, each way.” Cedric is still in contact with the community and talks to the chief on Facebook.

Visiting the Huaorani people

As tourism is a way for indigenous people to survive, the community invites people to stay with them. They’ll organise boat tours to see dolphins along the river and visitors pay a fair, ecotourism price for their stay. As they become more well known, more people who are visiting Ecuador want to experience a three or four-day stay with them.

“Tourism is good when it’s managed by the communities themselves,” Cedric says. “To have places and cultures renowned worldwide and to have people visiting these areas brings people together rather than dividing them, although the more remote they are, the more complicated it becomes.”

“Life is very simple in the forest and the matters are simple,” he concludes. “You don’t speak the language so they smile at you, so you look back at them and smile too. They understand that you’re there to have fun with them, and in everyday life they’re very happy people who laugh a lot. I invite anyone who wants to have a beautiful experience with beautiful people in a pristine environment to go to Bameno. But of course they will charge you for each day you’re there.”

Find out more about Cedric Houin’s ongoing project Contacted Tribes and watch the trailer for his film, which is in production.See more of his work at www.varialstudio.com.

All images in this article are by Cedric Houin.

Update: As of May 2016, the Huaorani Ecolodge is closed due to Chinese oil interests in the Amazon. Read more here.